Early on in All of Us Are Dead, student Lee Cheong-san exclaims to his peers as they fend off a wave of zombies swarming their suburban Hyosan High School, “It’s Train to Busan!” Another replies, “Why are they at school? They should be in movies.” With this tongue-in-cheek meta-reference to its notable film predecessor, it is a sign that the Korean zombie subgenre has well and truly sunk its grisly teeth into the popular cultural imagination.

First rising to global acclaim with the commercial and critical hit Train to Busan in 2016, the Korean zombie lineage also includes Netflix’s groundbreaking historical series Kingdom (2019), as well as films like Peninsula (Train to Busan sequel) and #Alive (2020). Through the grotesque figure of the zombie and its transitions between the human and the monstrous, these Korean shows have launched a terrifying critique of society in all of its moral wastes and systemic ills.

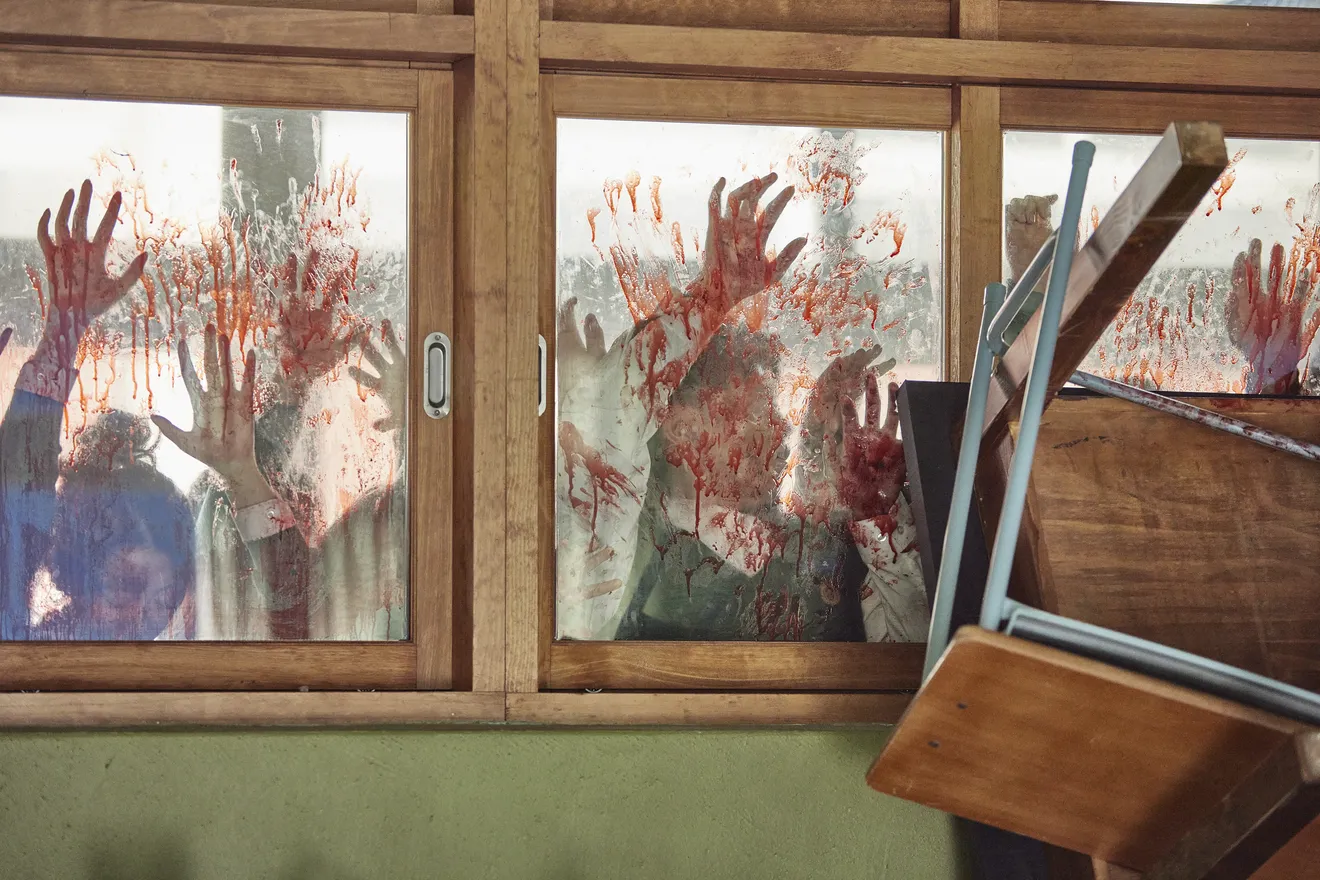

The high school setting in All of Us Are Dead marks a unique departure from previous locations used in Korean zombie shows. In the midst of the dread and destruction, the youthful setting opens up opportunities for adolescent banter and burgeoning love. We meet the loyal Lee Cheong-san, along with the buoyant Nam On-jo, who puts her survival knowledge learned from her firefighter father to good use. Class president and top student Choi Nam-ra is initially aloof and distant, though we later learn she is just fighting her own demons, like so many other students. Lee Su-hyeok and Yang Dae-su also make up the main group of students meandering through science labs, broadcasting rooms, music studios, the cafeteria, and teachers’ offices in their bid to survive and find a safe haven. What then is so wrong with the world here?

The immense pressure of the Korean high school setting — one which ends with the dreaded be-all-end-all university entrance exams, also known as Suneung — breaks and bends each student into despair differently. Some, like Choi Nam-ra, withdraw into isolation, earphones plugged in and eyes glued to her notes. Others, like Park Mi-jin and captain of the school archery team Jang Ha-ri, are overwhelmed by a defeated hopelessness about their future. A few more take out their anger on others and become school bullies — like the notorious Yoon Gwi-nam, who does not think twice about inflicting harm on others. The dehumanizing effects of fear become magnified by adolescent insecurities, reducing each young, vibrant soul into quivering shells of their former selves. In other words, the high school becomes a perfect setting for the mass production of a zombie population.

In the origin story of the zombie infection, a male student is frequently and violently bullied. His father, Mr. Lee, holds a PhD in cell biology and works as a science teacher in the same high school that his son is studying in. At wits’ end, he researches and creates the “Jonas Virus,” which preys on fear in humans and turns it into rage in a bid to make his son stronger and cope with the bullying. However, as these things usually go, the experiment turns out all wrong, and an infected hamster in Mr. Lee’s school science lab ends up biting a student, which unleashes the zombie virus upon the school and city.

The premise of the Jonas Virus — leeching onto human fear and transforming it into zombie rage — is a fascinating one but disappointingly underdeveloped in the series. One can imagine the various creative paths and adventures this premise could have taken the show, like using the absence of fear in certain characters to explain their resistance towards the virus or exploring possible “cures” to combat the Jonas Virus. Yet, All of Us Are Dead ultimately resorts to a constant stream of narration through grainy videos taken by Mr. Lee in his science lab and barely lit home. In these videos, we listen to him wax lyrical about the ideals of humanity, the monstrosity of evil that the Jonas Virus represents and the inescapable “system of violence” he was not able to save his son from. This turns All of Us Are Dead into a desperate survival show, and somewhere toward the second half of its breathless chase around the school, the 12-episode series begins to lose some of its pace.

All of Us Are Dead possesses the appeal of high school dramas like Riverdale and Euphoria. It captures in great detail the grotesque violence of high school social dynamics: the relentless gossiping and backstabbing, the unkind politicking and posturing of powerful in-groups and “cool kids,’’ and the festering churn of misery, which falls most heavily on the outcasts. While a few adults do their best to rein in the violence and protect their innocence, the students are largely left to fend for themselves.

The drama also sketches a wider portrait of society, depicting the chaos of government quarantine facilities and valiant attempts by authorities to cobble together an infection control plan. The implementation of martial law and life-and-death leadership decisions recall South Korea’s fight for democracy in the 1980s. All of Us Are Dead also captures the complex, moral struggle on the streets, where survival demands selfishness, even when the little bit of humanity in everyone implores them to limit harm. The series seems to make a damning pronunciation: enabled by adults, society’s systems of violence have seeped into schools and poisoned what should have been a bastion for moral goodness and innocence.

The power of zombies in fiction resides in their ability to compel our gaze inwards. In All of Us Are Dead, the zombies are teachers, classmates, archery teammates, and even best friends. Yet, in presenting these cruel circumstances, director Lee Jae-kyu’s take on the Korean zombie subgenre has chosen a most hopeful expression. While his predecessors have largely treated the transformation from human to zombie as a quick, crude one to register horror and revulsion, All of Us Are Dead lingers and dawdles on each transition, even for its minor characters. In director Lee’s world, there is something holy and sacred in this intervening space, in between the human and the monstrous, between sentience and savagery, between friend and fiend.

Many characters, after realizing they have been bitten and are about to turn into a zombie, offer acts of immense self-sacrifice in those precious few seconds before the last of their humanity blinks out into the barbaric darkness. One student throws himself at an onrushing group of zombies to protect his friends. An infected mother desperately ties herself to a door so that she will not cause harm to her baby after she turns. Another offers himself as a distraction to the zombie horde to buy survivors time to run away. Others wave tearful goodbyes as they distance themselves from their peers.

By repeatedly and earnestly holding space for both major and minor characters to demonstrate their humanity, All of Us Are Dead distinguishes its focus. This, combined with the drama-filled high school setting, helps the show carve out its own space in the crowded zombie pantheon. At the same time, it recalls the hallowed battle song that all great tales and stories possess: that we all inhabit both light and dark, good and bad, and that even in the direst of circumstances, we have the ability — and responsibility — to act in the interests of others.